Fragments of a Classical Twilight

John Martin Gallery, London, 2018

INTRODUCTION

FRAGMENTS OF A CLASSICAL TWILIGHT

John Martin Gallery, London 2018

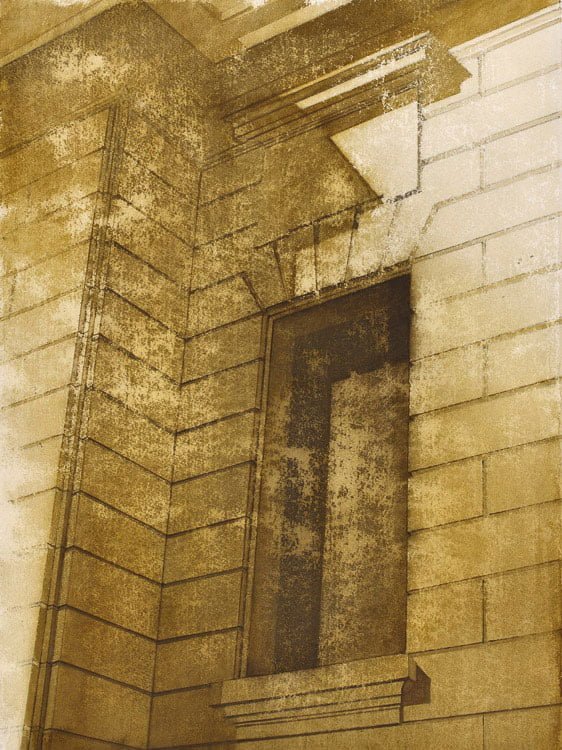

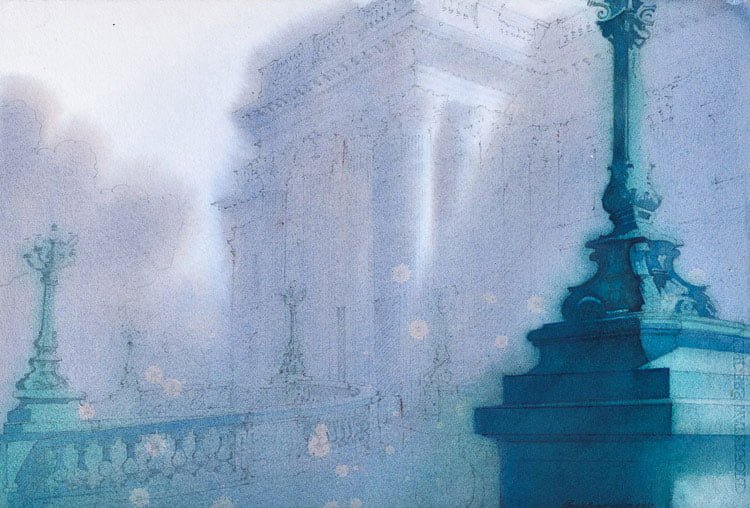

Walk down any street in any European or American city. If the principal buildings, the banks, the town halls, the hotels, are Classical in style they may not be as old as they look. Regent Street in London for example was not finished until 1927- the law courts in Philadelphia not until 1940. This style of civic architecture loosely described as Beaux Arts, originated in Paris in the 1830’s, and seemed to coexist alongside the gothic revival. It has become so familiar that we take it for granted, and yet, combining as it does, the accumulated skills of millennia with modern methods of construction it is a uniquely important part of our heritage that comes as close as anything to the splendour of ancient Rome. Indeed although we affect to scorn the Victor Emmanuel monument, which dates from 1912, some scholars consider it to be a fairly authentic representation of that imperial city. This is a very public architecture designed not only to be enjoyed by the public but perhaps more importantly to dignify that public.

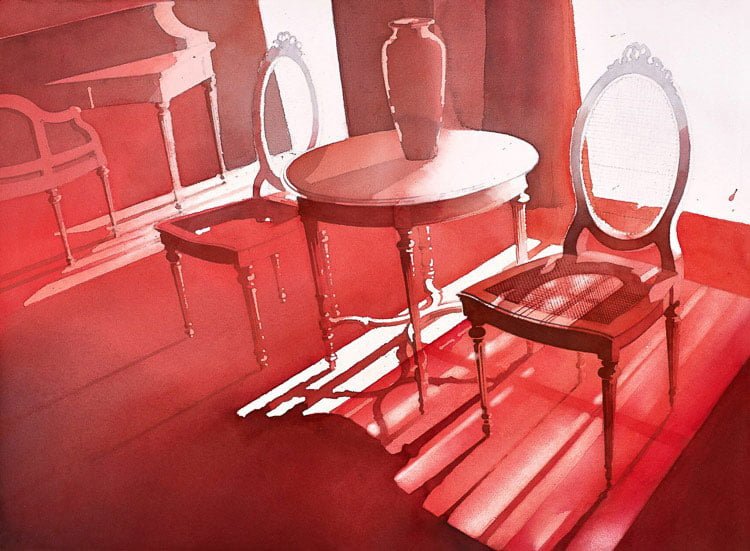

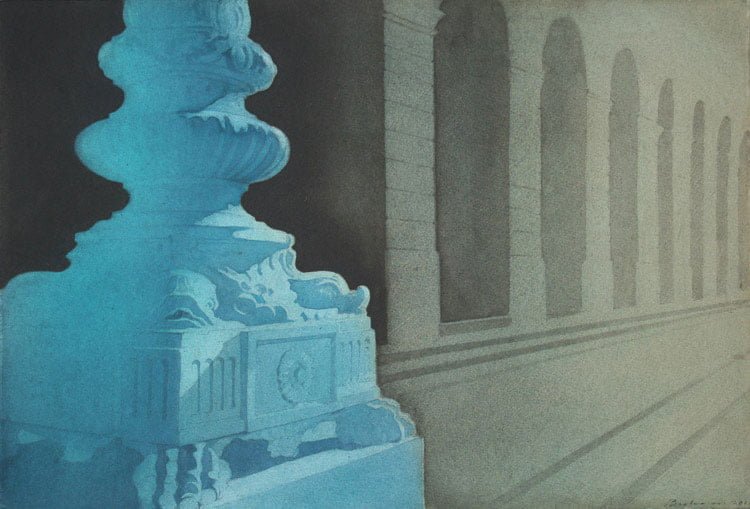

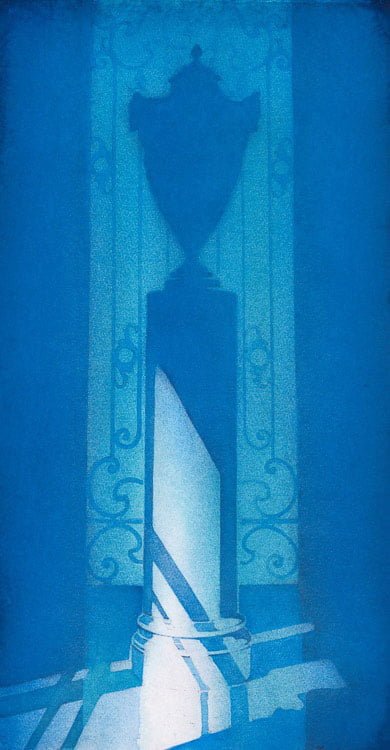

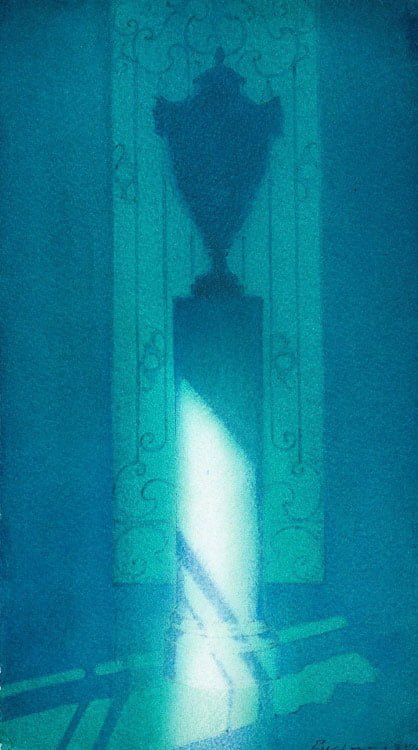

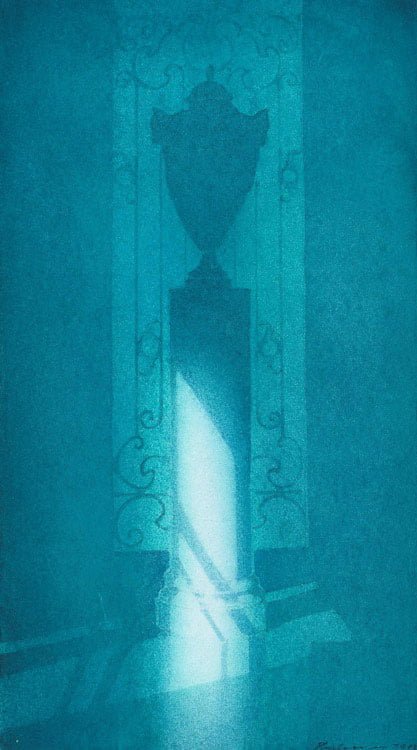

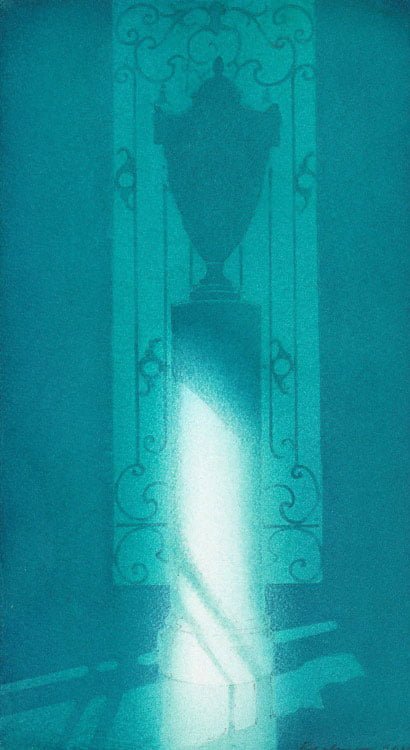

The style reached an exquisite perfection with Richard Morris Hunt’s work at Newport Rhode Island at the turn of the last century, but was brought to an abrupt close there by the twin disasters of the sinking of the Titanic And World War I, which affected so many of its residents. The atmosphere of doomed hedonism was perfectly captured by F Scott Fitzgerald in the Great Gatsby which was filmed at Rosecliff, Newport. My Blue Urn series serves as an elegy to that generation.

Nor did the modernists, later on, see any place for such apparently anachronistic behemoths and the style’s most notable casualty has been McKim, Mead and White’s 1910 Penn station in New York . Its gigantic cavernous hall was modelled on the Baths of Caracalla and when, amid much controversy, it was demolished in the 1960’s, the architectural historian Vincent Scully lamented that while formerly “One entered the city like a god. One scuttles in now like a rat.”

However, if we take 1900 as the absolute zenith of the last classical age we can see that Classicism stages a faltering resurgence every forty years or so. In the 1940’s there was a fashion for the New Regency style and the 1980’s, when I started my career, saw the rise of Postmodernism most obviously manifested in New York by Philip Johnson’s 1984 AT&T Building and in London by the work of Terry Farrell. We’re a few years away from another forty year cycle, something I have been eagerly anticipating. Classicism, especially in the digital age, is always capable of reinvention.

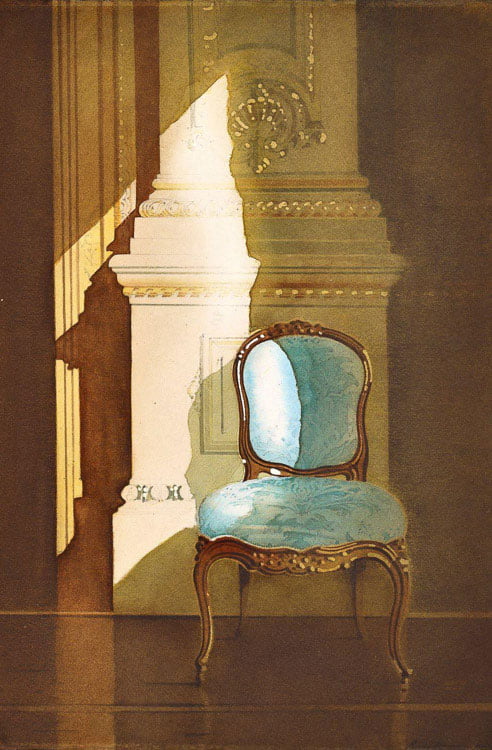

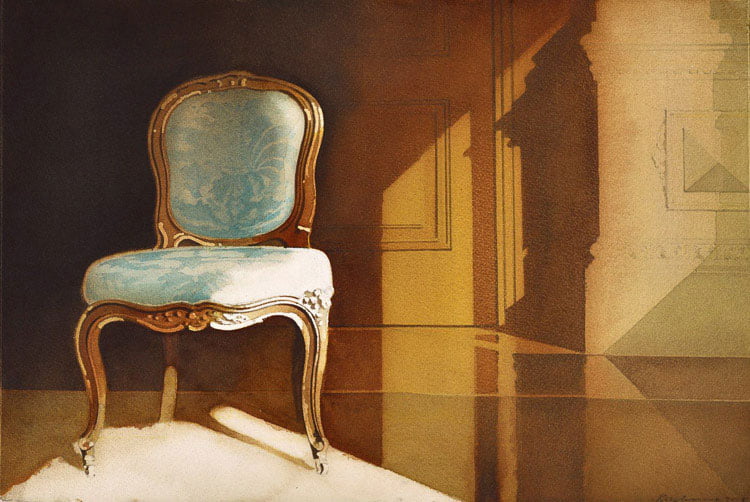

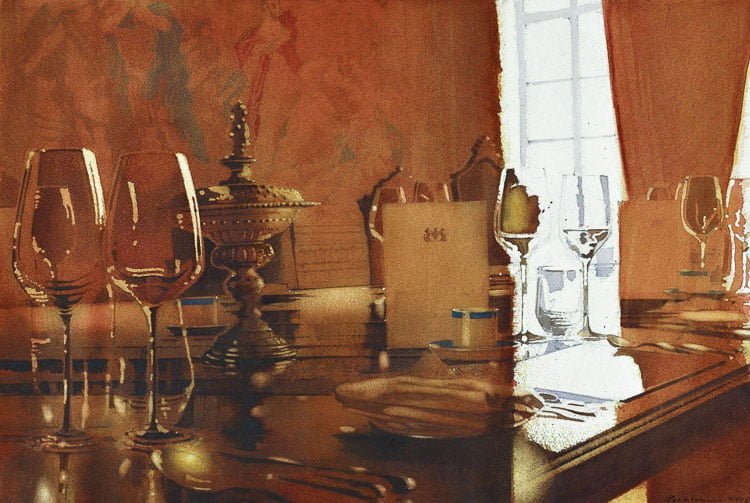

In celebrating 19th and early 20th century Classicism I have not been systematic and there are of course many omissions. I have just painted locations as I have come across them. It is perhaps surprising that the ancient London Livery Companies should have provided such rich subject matter and yet both The Drapers’ Hall and the Goldsmiths’ Hall were extensively remodelled in a Classical style in the 19th Century. The Drapers’ by Herbert Williams and John Crace who had formerly worked with Pugin in the gothic idiom on the Houses of Parliament. Goldsmiths’ Hall was reconstructed by Philip Hardwick who was responsible for that other great lost Classical railway icon, the Euston Arch, hopefully soon to be reconstructed.

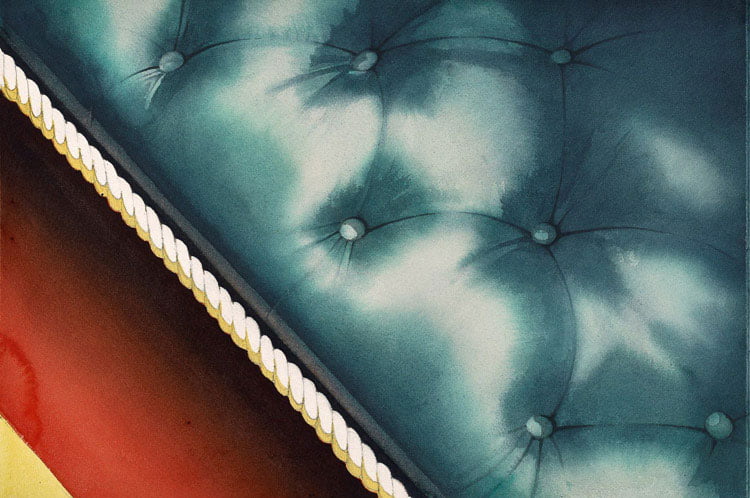

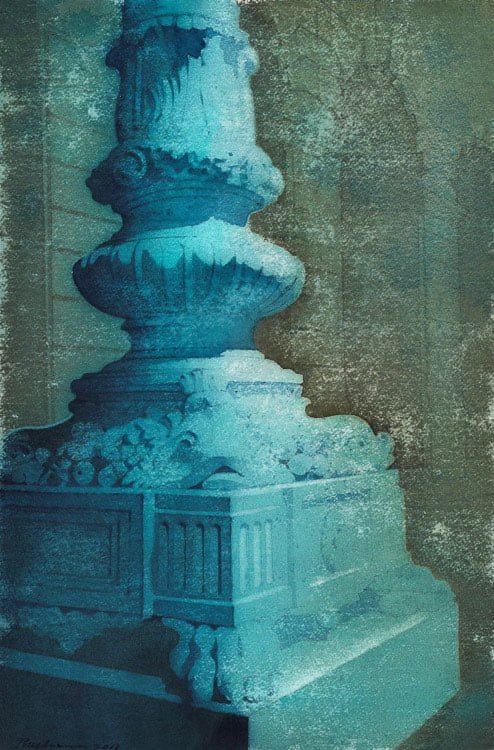

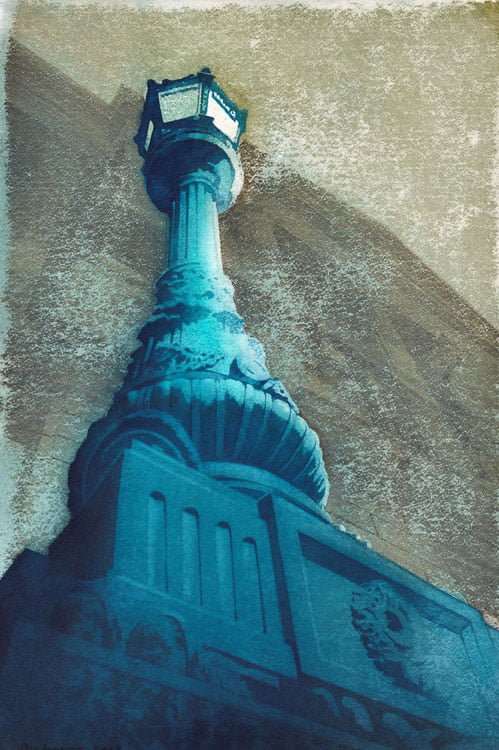

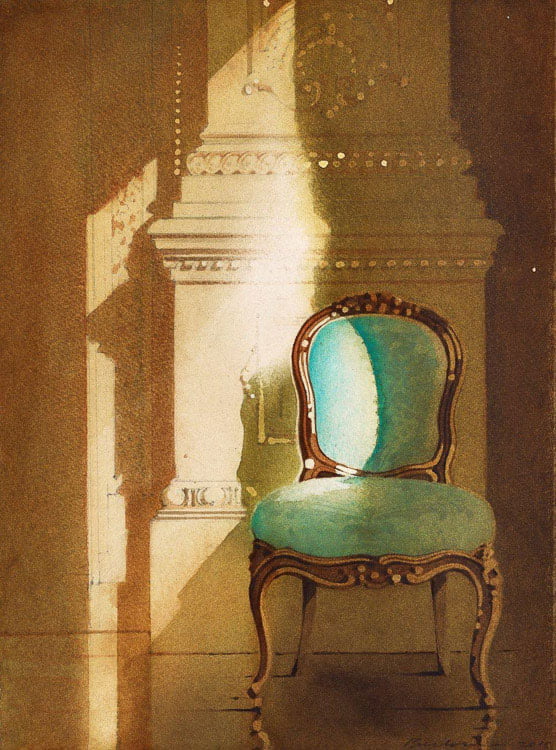

There were links across the ocean in colour as well. The damask chairs in the Drapers Company were the same cobalt turquoise as the verdigris stained bronze lampstands in Newport and Joseph Bazalgette’s lion masks on the Thames Embankment.

Two artists will see the same subject in different ways. I found myself sitting in the same spot as Monet, underneath Cleopatra’s Needle, but while he had rendered the bronze lions as mere slashes of viridian and concentrated upon the jetty and the Houses of Parliament I found myself doing the opposite: erasing everything except the embankment and studying the lion masks in the greatest detail.

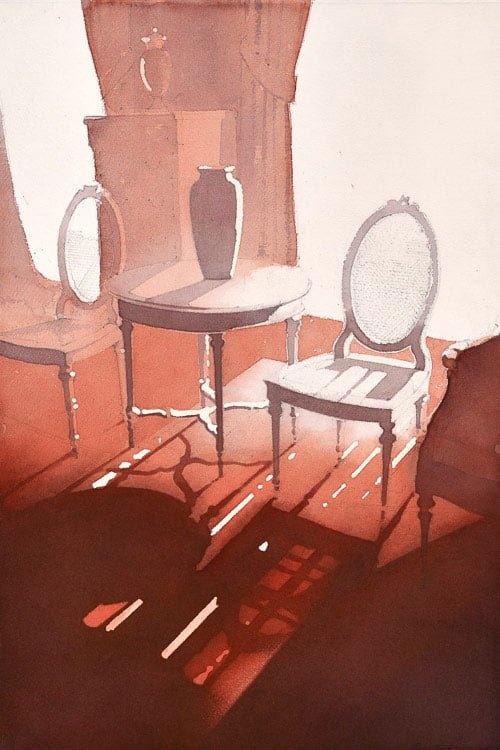

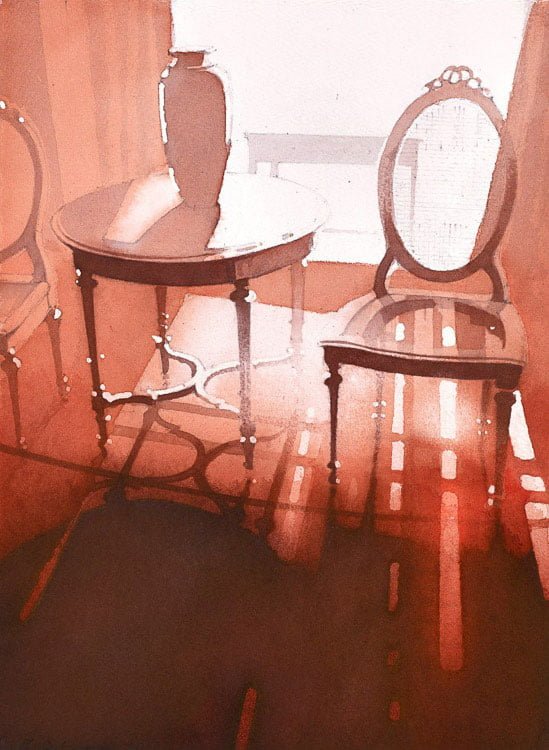

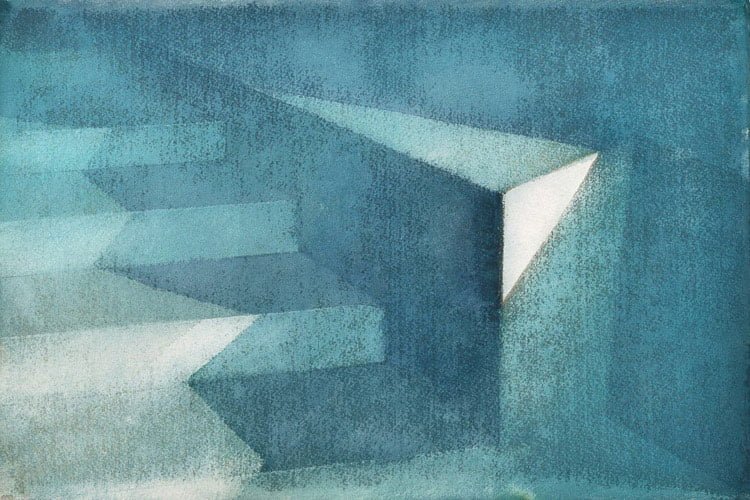

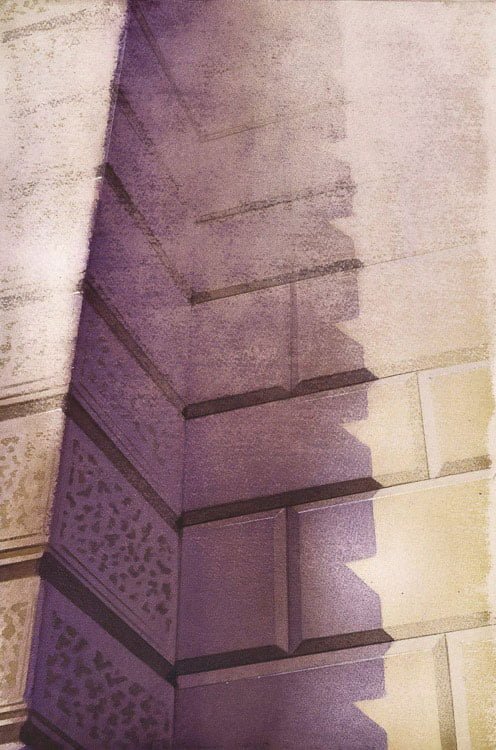

At the heart of my work is light and how it enters a room. In Newport it is blinding, bouncing off the sea and flooding the rooms: almost dissolving the furniture in its intensity. In the Livery companies it is quite different; surrounded as they are by skyscrapers, the light is much more elusive, revealing itself as tattered fragments momentarily piercing the gloom as the sun emerges from behind the Gherkin or one of its neighbours. Of course as a watercolourist light is always revealed never applied. To that end my paintbox has some unusual implements: sandpaper and hogs hair brushes, compressors and sprays as well more conventional materials which are all used variously to summon up the spirit of the place and era in a way that speaks to us now, not just of loss and regret, but of the next Classical revival.

Hugh Buchanan 2018