Early Exhibitions

The Francis Kyle Gallery, London, 2006

REVIEWS

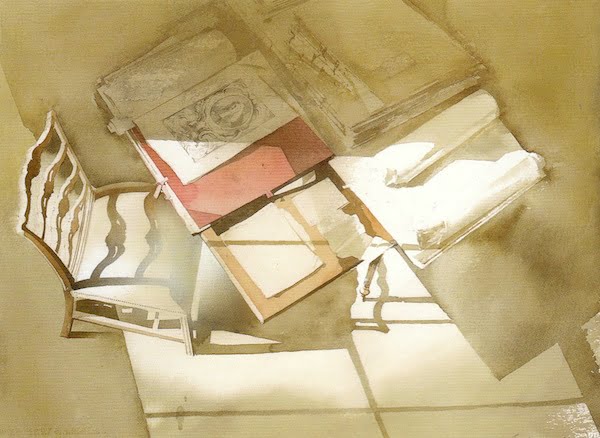

In fact many of the later works in her collection were gifts. There is a particularly intimate painting by the Scottish artist Hugh Buchanan, Desks at Royal Lodge, commissioned by a large group of members of the Royal household for the Queen mothers 100th birthday in 2000. In the foreground is her own desk in the saloon. A photo of her husband is propped casually against a vase of garden flowers. It is not only hugely technically accomplished but somehow captures the warmth and affection in which the Queen mother was held by the royal household in particular and the nation in general.

Anna Burnside THE SUNDAY TIMES MARCH 2005

The Francis Kyle Gallery, London, 2006

INTRODUCTION

By HUON MALLALIEU

Often in his work Hugh Buchanan seems to hint at things just beyond the edge of the mind. Kipling’s ‘ The way through the woods’ and de la Mare’s ‘The Listeners could have been written to accompany his watercolours.

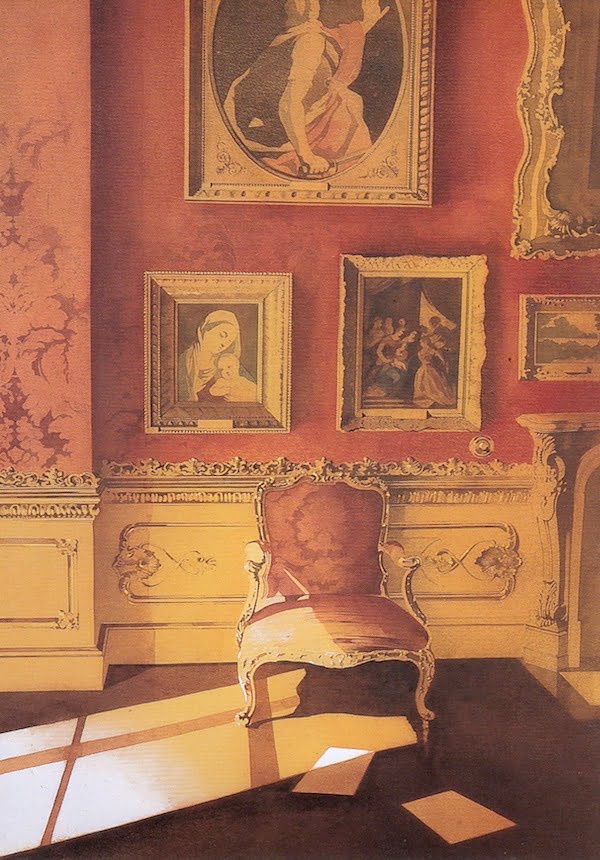

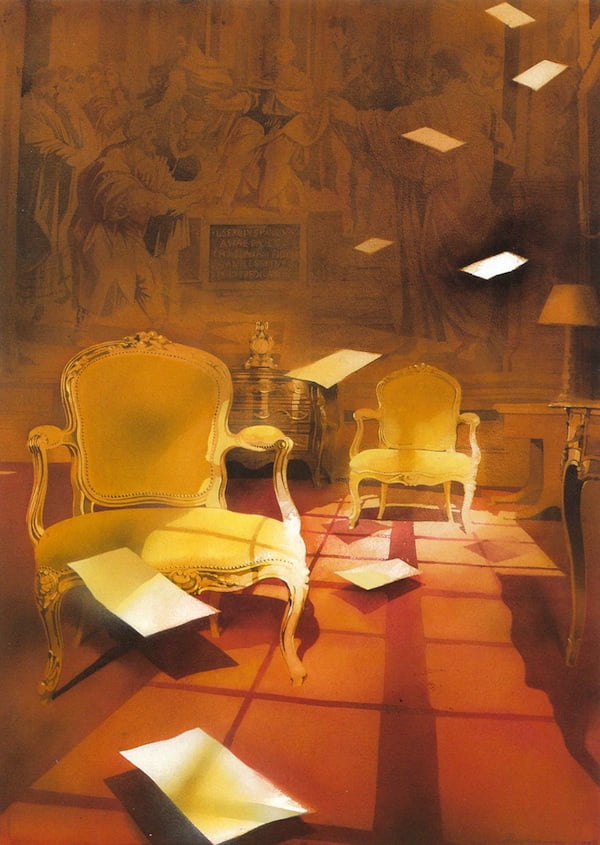

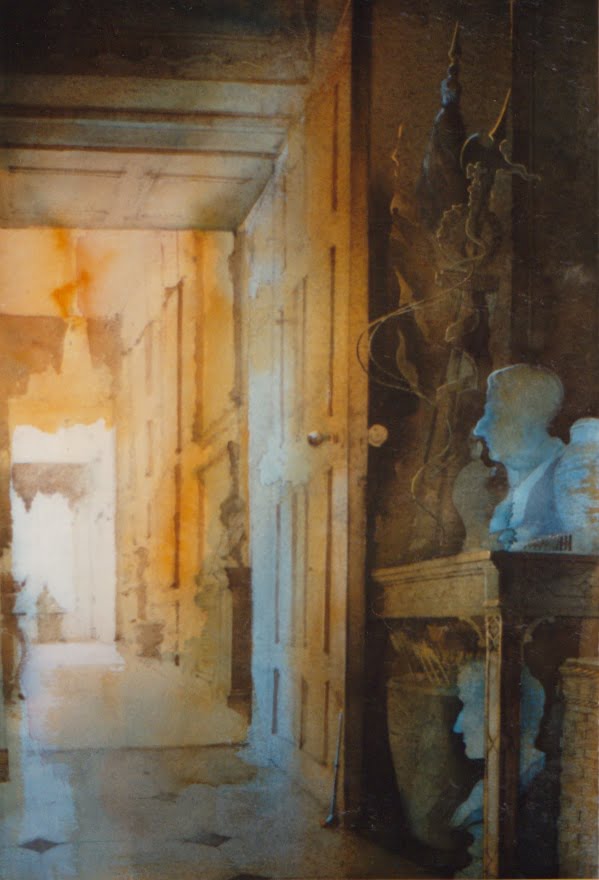

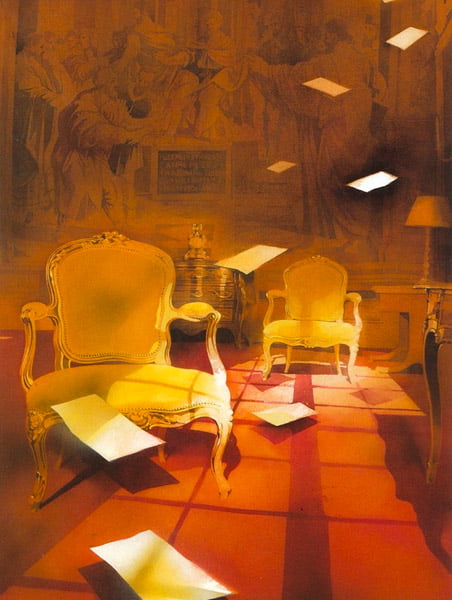

Living figures rarely appear although he is a highly accomplished draughtsman, but the corners of his great houses are not empty. Anyone who has visited Denis Severs’ remarkable Spitalfields house will know the sensation: the family has left just a moment before, and will return as soon as we ourselves are departed. In the present show the Osterley chairs suggest this most strongly. Do we not see motes dancing in the light disturbed by the flick of a coattail?

Just as Kipling and de la Mare were poets who built on tradition, and their work was informed by the past, so Hugh Buchanan builds on and extends the great watercolour tradition of this country. Two hundred years ago, when the ‘Old’ Watercolour society was founded, and Turner and Cotman were making their way there was considerable controversy as to the legitimacy of using white body colour for highlights, rather than allowing bare paper to shine through. Translucency is the essence of watercolour it was argued. Hugh Buchanan goes beyond the old quarrel, using both paper and acrylic for highlights, but airbrushing to blend and intensify. He also uses a great array of brushes, and, unusually, working from dark to light to build up his sandwiches of wash.

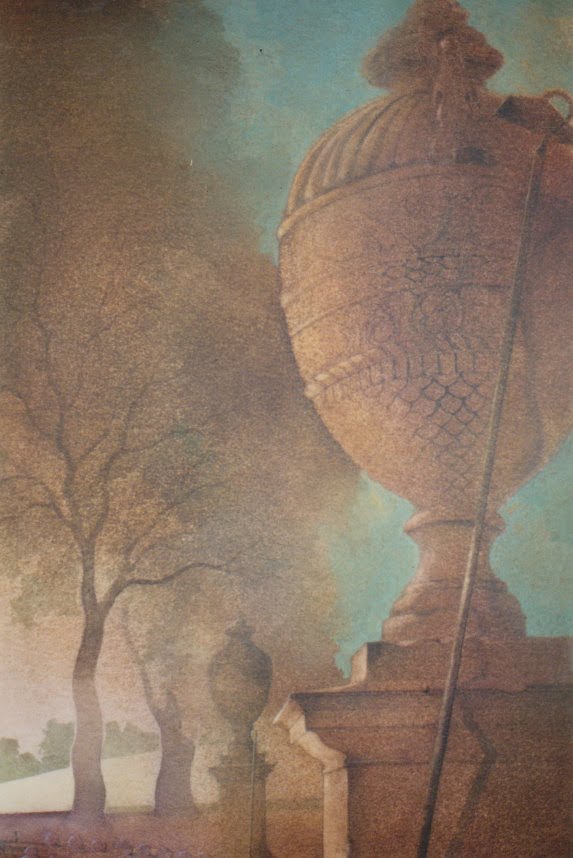

He transcends another old concern; that really large watercolours rarely work. Once again the admixture of acrylic helps. The largest here , Tapestry Boughton, measures 58”x 40”, a touch over ‘Extra antiquarian’, the second largest traditional drawing sheet size, and far bigger than was generally considered practical.

The national trust, private owners of great houses, present and future generations of lovers of art and architecture, all have reason to be grateful to Hugh Buchanan. His work gives life to the houses and contents in a way that no photographic record could.

REVIEWS

It was raining: I walked into the Francis Kyle Gallery but I nearly walked out again. Watercolours of furniture? Pretty watercolours of furniture in stately homes ? … I ended up staying long after the rain had stopped.

Hugh Buchanan has worked on commissions for the National Trust and his work appears in the collections of the Royal family; Prince Charles invited him to paint a series of interiors of Balmoral as well as Highgrove. Established as an artist of the establishment he was also commissioned by the House of Commons to paint interiors of the Palace of Westminster. However this pedigree hasn’t stopped him taking risks, bucking convention here in his tenth exhibition at the Francis Kyle Gallery.

Hugh Buchanan’s work takes us back to traditional craftsmanship whilst taking us forward in altering the traditional format and focus of watercolour. Art when it was previously ecclesiastical in scope and an exercise in craftsmanship stood or fell on easily comprehensible merits or faults. A faulty conceptual idea is more easily obscured in the method of its representation; modern art becomes increasingly a history of ideas. It’s therefore rare to see an artist who successfully combines the two, depth of concept with depth of technique. In much the same way as surrealist photography embraced German New Objectivity, transforming the mundane into vitalised abstraction or forcing us to look with unprecedented intensity at objects we thought were familiar (Andre Boffards big toe for example), Buchanan has zoomed in on interior details defying the rules of usual interior compositions, revelling in the texture of fabric; upholstery weave coruscates on paper. Line is eschewed in favour of modelling form using light and shadow. One can see how light is used to pick out as well as obscure detail by its brilliance. Tonally rich, richly atmospheric; his work shows historic interiors in a new way, un-cliched and surprising. Unusual angles of view are deployed; diagonals, significant underviews and overviews are all utilised. Its almost as if he wants to bring fresh air into these old houses; in Sudden Breeze Boughton, papers presumably blown off a desk by an unseen open window, are suspended in mid air. Yet there is no sense of movement, its almost as if the air in the room has become gelatinous. There is a feeling of heaviness. The weight of history. Buchanan has a lot in common with European avant garde photography of the 1920’s.

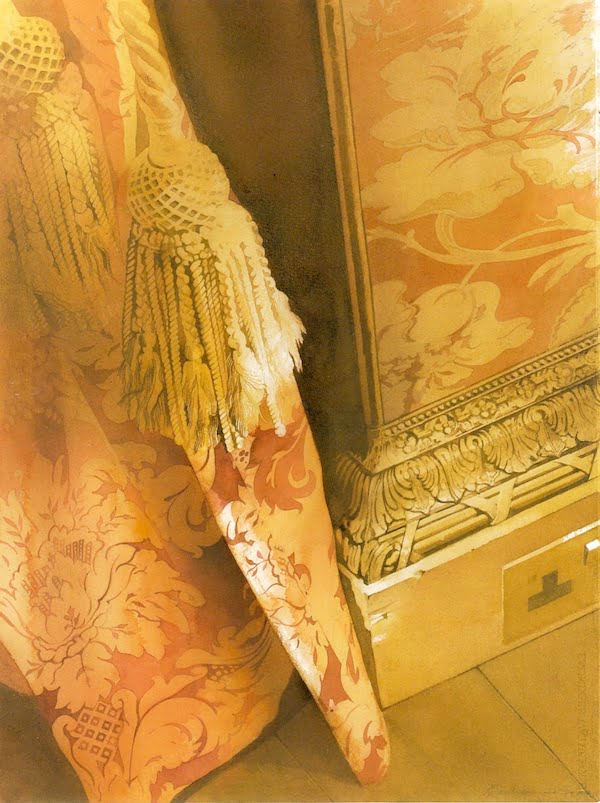

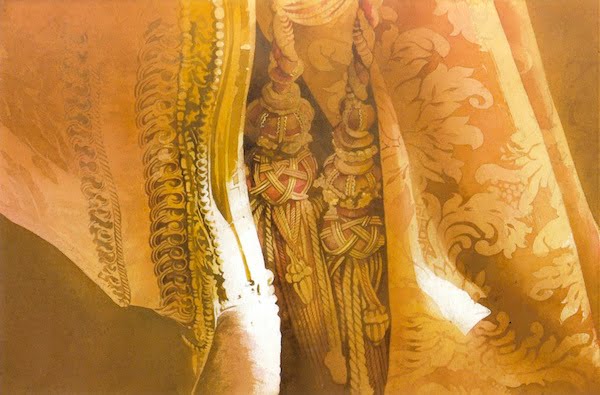

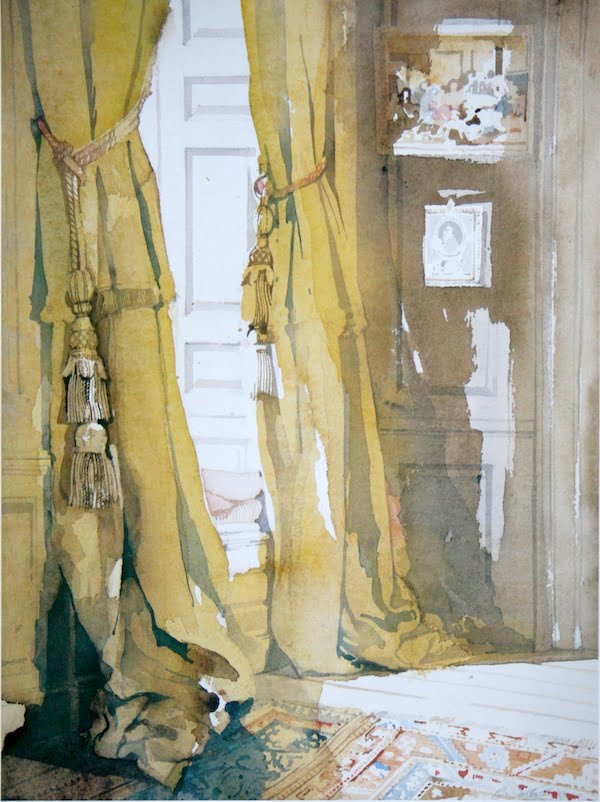

Stately homes might be deeply traditional subjects but his choice of emphasis certainly isn’t. Robert Adam’s Syon House is evoked in 13 Amp Socket at Syon,a work that glories in the detail of an electric socket , a scuffed skirting board touched by the tip of a brocade curtain. By drawing your attention to incidental details he conjures up the atmosphere of the whole in a genuinely innovative way. The subject is presented with all the freshness and vitality of a glance; the edges of the work are activated and one gets the sense of the composition extending beyond the frame. Adam worked holistically to realise minor architectural details as part of an harmonious architectural whole. Buchanan takes the same approach- one cannot fail to be aware of the details in his work suggesting the greater context.

With Buchanan’s watercolours it helps to know a little bit about the medium in order to realise how well he has mastered it and how he has taken it forward. Like Joyce with his manipulation of the traditional literary voice, Buchanan has augmented traditional watercolour technique by incuding methods such as airbrushing and materials such as acrylic. Each work is an exercise in virtuosity. The scale of each in itself is astonishing, the largest work, Tapestry Boughton is a metre across and almost a metre and a half in height. Like Holbeins execution of the carpet in the Ambassadors, areas of material are left bare to constitute highlights – no mean feat, considering the vast expanse of paper and that Buchanan doesn’t use masking fluid. The occasional spill only serves to highlight the overall application of skill, drawing the viewer’s attention to the demands of the medium and the medium itself.

The only thing that animates, that appears naturalistic, is the light.

© Stella Pe -Win 2004

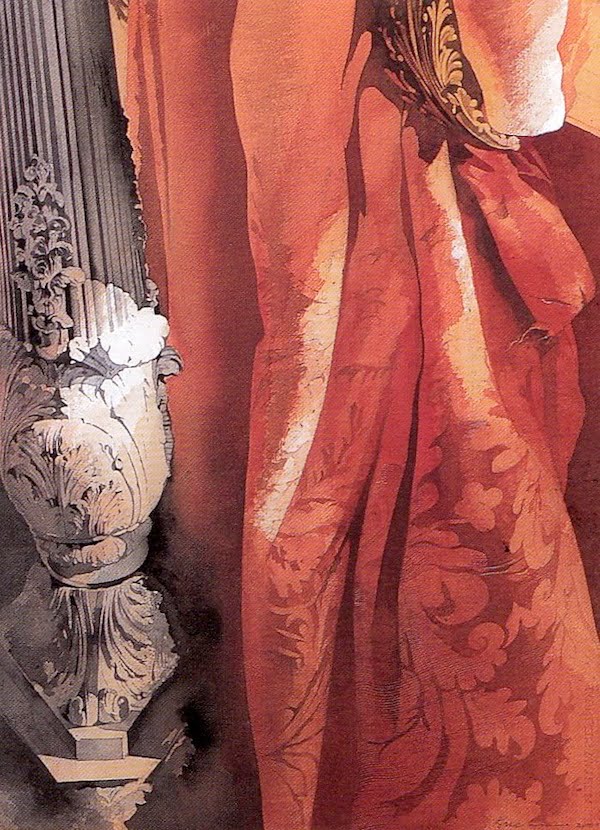

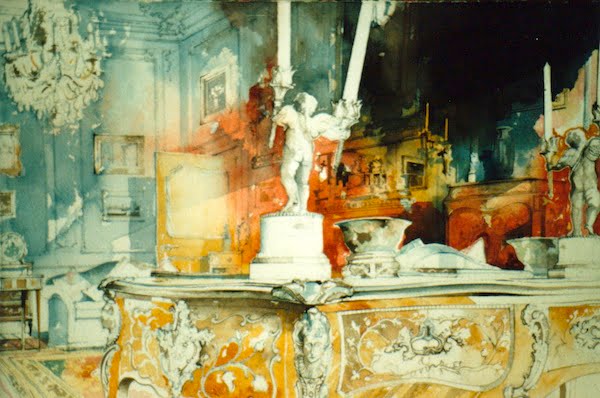

This exhibition is devoted to interiors at Syon , Osterley, Harewood, Boughton and Blairquhan in Scotland. But these are no ordinary watercolour impressions of picturesque interiors; to begin with they are enormous- Tapestry, Boughton is nearly six feet high, and their choice of subject matter elevates details that are usually overlooked. Reflected Light at Syon for example is a close up of two elaborate tassels sheltering in the baroque folds of a brocaded curtain. There are wainscote eye views of architectural details; miraculous descriptions of tapestry, gilt, ormolu and polished wood rendered with an accuracy that manages to preserve something of the freshness and luminosity of watercolour; and observations of the dramatic transient fall of sunlight.

THE WEEK Nov 2004

Buchanan’s mastery of perspective is expressed in his predilection for oblique and unusual viewpoints that reveal only part of his subjects. This penchant he shares with Robert Adam who believed that ‘the more you keep people from seeing the more their imaginations have occasion to work’ . The two also share a preoccupation with the effects of light and shade. Which are in some ways more dramatic in Buchanan’s Osterley chairs than in his view of Adam’s sculpture gallery at Newby shown last year.

The emptiness of his chairs – alone or in pairs , seen close up from below or above- is quite suggestive, a little spooky and unsettling. The solitary chair at an open door is clearly expecting an occupant; but what about the same chair before a closed door? The two chairs facing left towards the light seem to be waiting for a show to begin; another pair seem to loom up in a defiant and threatening manner, made all the more disturbing by the bleaching frontal light and the distorted perspective in which walls appear to be falling backwards.

Although Buchanan manages skilfully to capture the different textures of the tapestries, the carved and gilt wood chair frames, mahogany doors and ormolu door furniture, realism is not what he is about. In reality the Osterley chairs are small and refined; in Buchanan’s large watercolours they are, in a manner of speaking, larger than life creations of his imagination.

EILEEN HARRIS APOLLO

In watercolour, Hugh Buchanan renders the surfaces of gilt , wood veneer, tapestry and brocade with an extraordinary perfection and drama. The subjects of this exhibition put his skills to the test: ivory inlay on doors, light on tapestry chairs, tattered stretches of brocade damask wallpaper and flaking gold leaf. Huon mallalieu observes, ‘There is in these furnishings a seductive, narrative element which finds expression, for instance, in the vignettes of rustic children on the chair backs from Boucher’s ‘Jeux des enfants’, a sequence of embroidered works and tapestries produced at the Gobelins workshops and destined originally for Madame de Pompadour’. A human presence is mysteriously evoked in Hugh Buchanan’s unpeopled interiors, as if the inhabitants have been granted their privacy. While remaining true to the craft and tradition of watercolour painting, in his recent work Buchanan has extended its suitability with great proficiency.

STUDIO INTERNATIONAL Nov 2004

The Francis Kyle Gallery, London, 2002

REVIEWS

Truly to convey the character of an interior, an artist needs to marry an architects eye for form and detail with an understanding of the spirit of the place. In Mr Buchanan’s new works both are present in abundance, particularly in his images of Newby Hall and Castle Howard.

Mr Buchanan cites artists of the past whom he believes were successful in handling interiors. Cotman is a particular favourite. But it is not only the Brittish in whom he finds inspiration. ‘Piranesi casts a huge shadow over everyone who’s ever tried to paint an interior’. And like Piranesi, Mr Buchanan’s paintings are less about architecture than light. He cites as precedent William Chambers’s sections through York House. ‘What amazes me is how few people picked up on his use of shadow. How he knew that light defines a room’. Mr Buchanan’s paintings are all about how light defines objects. More specifically, about the way in which objects disappear into light. His work has always been to do with the movement of architecture in light and more than ever these latest works change before your gaze.

Tapestry Chairs at Newby Hall is a perfect example of the harmonious union of object and atmosphere; a hugely powerful piece which points I hope to the artists future direction. ‘ I think the chairs suggest a human element’ he says. They are certainly anthropomorphic, but there is a pervasive humanity in these works. They have a sense of people past and present as an unseen yet implicit presence.

Iain Gale COUNTRY LIFE

‘Astonishingly evocative Interiors.’… In Buchanan’s paintings even inanimate things acquire a sort of poignancy; in warm tones and exquisite washes of paint his depiction of light signals the fragility of damask and parchment, the erosion of sandstone and the glow of polished wood.

THE WEEK Jan 2003

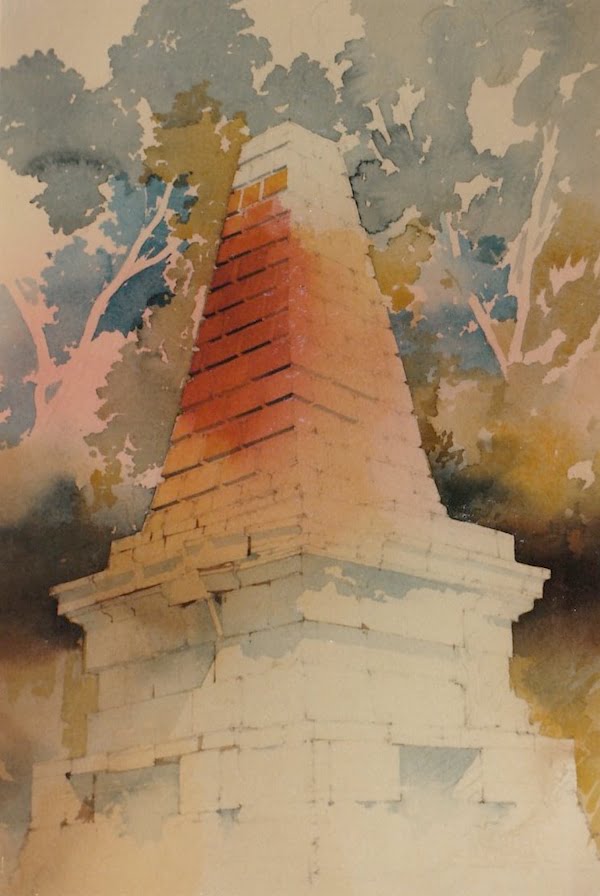

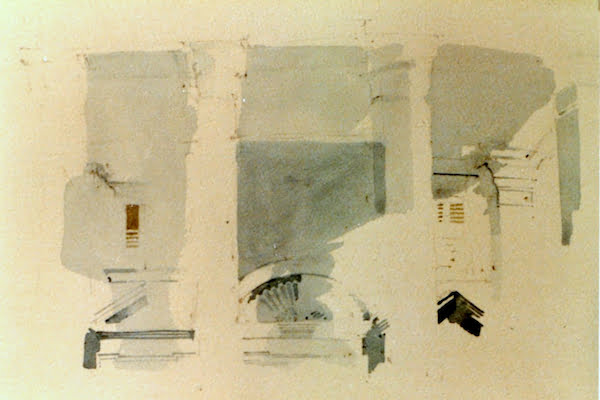

Buchanan moves through a light washed world of stone. His architectural watercolours capture the tranquil orders of classical structures. Working in Newby Hall and Castle Howard in Yorkshire he leads viewers into a pale land of sun filled domes and decorative pillars. Manuscripts lie on a desk unattended in the Muniment Room . As Buchanan himself explains his art aims to capture “the fragility of damask and parchment, the shininess of floors, the flakiness of gold leaf and the coldness of marble”

Rachel Campbell Johnston’s Best London Shows THE TIMES 2002

The Francis Kyle Gallery, London, 2000

INTRODUCTION

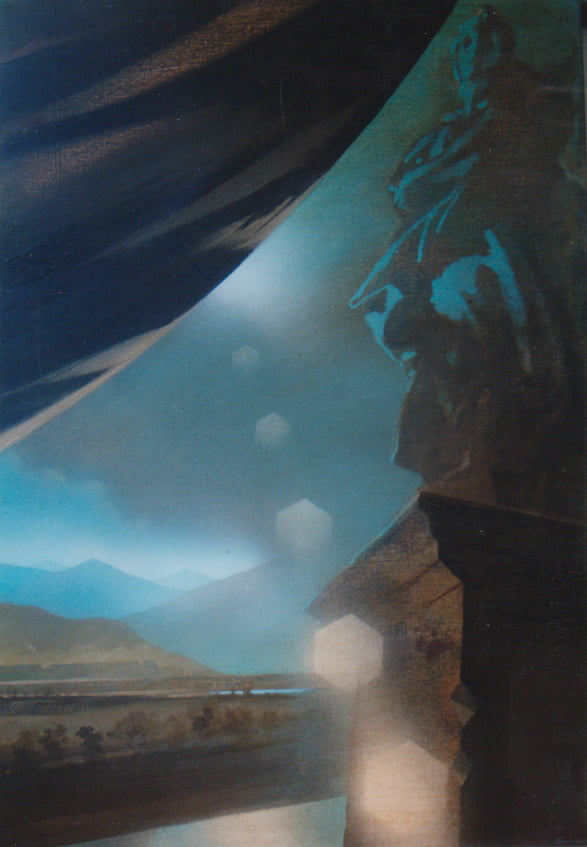

Catalogue Introduction by SIMON THURLEY

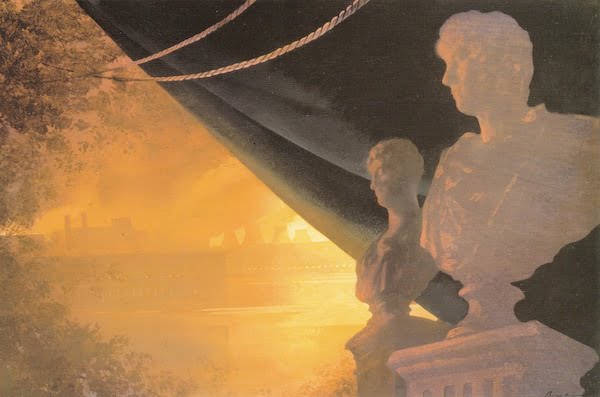

Hugh Buchanan’s paintings that at once surprises, while remaining entirely familiar. His latest show pushes this to the very limit, for as well as much that is central to his previous concerns Buchanan sets off in a startling new direction. In his watercolours a new tension has emerged. Gone are the dark smoking industrial plants, framed by a lost classical civilisation, from Abreviations of Time, gone too are the adjuncts of construction from The Eloquence of Shadows. Buchanan returns to a much purer classical vision, but one , for me, much more ambiguous. The watercolours transcend time and geography. We cannot tell whether we are admiring the neo-classical splendours of Vienna, the grey sobriety of classical Edinburgh or the achievements of ancient Rome itself. As ever there are no people to guide our way and even the busts stand silent and unhinting. Perhaps the central watercolour is the Frontier . Heavily evocative of Hadrians Wall it links the watercolours of Hadrians Villa with St Andrews Square, Edinburgh. As tick rests against the base of a pillar. Is this the staff of a Roman philosopher, of a legionary on Hadrian’s Wall, or is it the artists stick in his native Edinburgh? Somehow, though the subject of many of his watercolours is so distant, they all seem to be at home. Buchanan has returned to his Scottish roots.

The Francis Kyle Gallery, London, 1998

INTRODUCTION

Catalogue Introduction by IAIN GALE

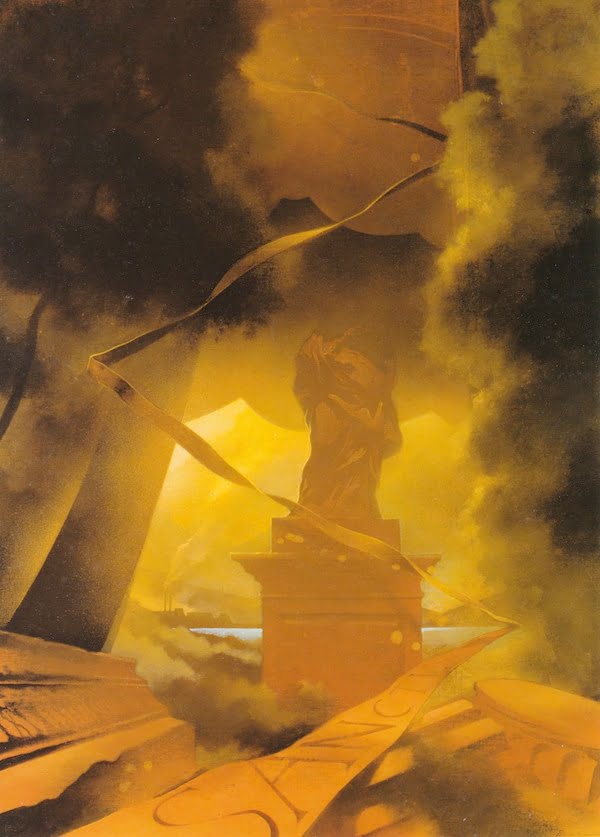

In one of the most instantly engaging works here, Gathering Breeze, some plans have blown away in the wind from a waterside parapet on which rests a solitary spear. It is only when we look closer that we realise that the plumes are those of a cooling tower and the plume of smoke across the bay is not of Vesuvius but a heavy industrial complex. The past has become inextricably intertwined with the present. Indeed the conventional notion of time seems in all these images somehow superfluous. Nothing is stable; nothing either content or enabled to remain in its fixed time.

REVIEWS

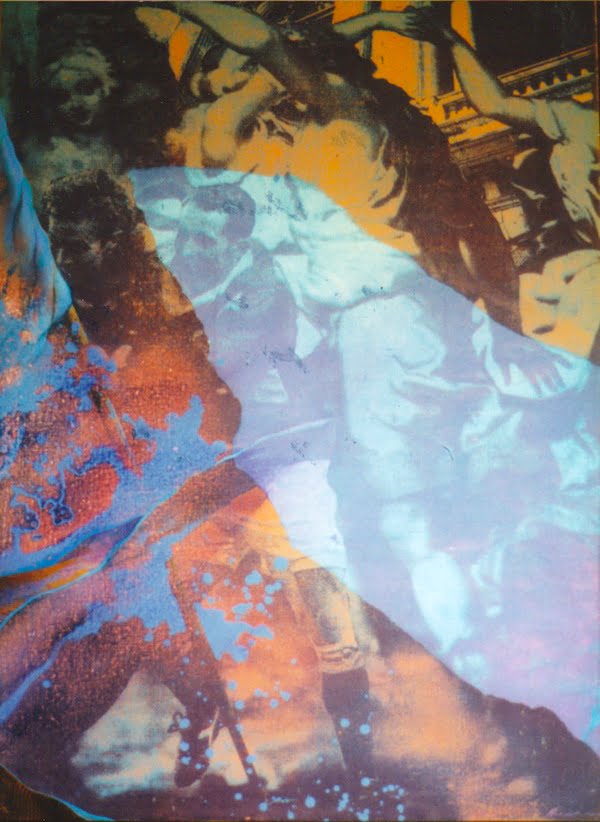

Known for his commissions for the National Trust and the Prince of Wales, Hugh Buchanan appears less representational, more meditative, in his new work. Computer –generated images, screen printed onto board and then painted over create strange hybrid scenes in which the ancient guards the gateway to the innovative. Behind the visionary images Buchanan is posing serious questions about the nature of our architectural landscape and its legacy

RACHEL CAMPBELL JOHNSTON The Times 1998

Buchanan has created a remarkable series of paintings. Each one exists as an emotive compression of time, landscape and memory; an analogue in which the layers of history have been peeled away to reveal the perennial concerns of the human condition. Essentially poetic in both form and function they seem most clearly to echo the words of TS Eliot

Go, go, go said the bird; human kind

Cannot bear very much reality.

Time past and time future

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.Buchanan has achieved a difficult crossover between the techniques of the traditional painter (watercolour was his first love) and modern computer technology. The resulting images are at once both contemporary and rooted in the language of art history. The works have an immediate compelling beauty and an intriguing sense of allegory; in one work for example, the bust of a Roman emperor rises quite naturally above the silhouette of a smoke shrouded power station. Buchanan displays an enviable understanding of the vagaries of light and shadow. With a subtly manipulated neo – classicism he points the way towards a truly original vision of contemporary art.

THE WEEK November 1998

The Francis Kyle Gallery, London, 1996

INTRODUCTION

Catalogue Introduction by JOHN RUSSELL TAYLOR

To judge from Hugh Buchanan’s art, past and current, it is easy to guess that he has been obsessed with the past all his life. But of course, you might say; after all he has spent a lot of his career painting stately homes in watercolour. True enough. But even in those works it is never a simple case of nostalgia, mooning sentimentally over the glories of some semi- fictional Golden Age, from which we have all sadly declined. On the contrary, it is the ability of the present to subsume the past, the ability of the past to remain a vital, living part of the present that seems to give him the greatest hope for the future.

All this has been implicit in the country house watercolours, easy enough to read by anyone who gives them more than a superficial glance. But it comes right to the fore in his newest work which indicates an astonishing advance on what has gone before and yet remains completely consistent with it, a development rather than a revolution. This time the works are much bigger, and use about every medium but watercolour. Across their intricately assembled surfaces unroll screenprinting , collage, acrylic and oil combined with all the latest computer technology. ( In this alone we can see that far from rejecting the present with cries of horror, he welcomes it with open arms, and if we are in any doubt we have only to note the image of a laptop computer cheekily nestling in the bottom left hand corner of one of the more elaborately baroque compositions).

The old preoccupations of course persist. The love of piranesian perspectives, the intricately sculpted columns and urns, the drapes, the drifting rose petals. The fascination with architectural history is unmistakable . but there are other elements, equally important. More or less buried, more or less visible in many of these pictures of modern soccer players, and if in some of the pictures they merge unpredictably into classical sculpture the effect is to make them heroic rather than to diminish the other half of the equation. There are pylons which may be seen as menacing, or may still carry the thrilling aura with which they were invested by thirties poets. Pollution there undoubtedly is, but it seems to be part of the conundrum posed by Antonioni’s Deserto Rosso : the yellow smoke may kill the birds but does that make it any less beautiful?

The central point that Buchanan seems to be making is that all experience is layered, the past and present somehow mysteriously co- existing. It is appoint made in a very different way by David Jones in his finest most intricate drawings, as well as in his writings like In Parenthesis and The Anathemata which constantly emphasise that the present is built out of the past, or written on the past with elements , palimpsest-like, peeping through. The point is made physically in Buchanan’s new works by the way the image, and even the surface upon which it is formed is pieced together from pre existing materials. But one does not need any close technical inspection to respond to the total effect. Apocalyptic or triumphant? It could be either, it is probably both.

REVIEWS

Combining baroque architecture with imagery borrowed from popular media and a variety of textures derived from frottage, Buchanan, better known for his architectural watercolours seems to be moving in an interesting direction, tackling issues of cultural history and politics and the self awareness of the Scottish nation.

Iain Gale SCOTLAND ON SUNDAY 1996

Buchanan should not be mistaken for a mere draughtsman. His paintings are imbued with haunting romanticism; opera sets stalked by ghosts.

Celia Lyttelton TATLER 1996

The Francis Kyle Gallery, London and the National Trust at Petworth, 1994

INTRODUCTION

The Painter as Poet Giles Auty

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present

Footfalls echo in the memory

Down the passage which we did not take

Towards the door we never opened

Into the rose garden

TS Eliot, Burnt Norton

Although widely thought of and admired as a painter of architecture, Buchanan does not deal primarily in great facades or vistas as topographical painters habitually did from the 17th century onwards. He treats architectural detail with respect yet often seizes upon and isolates it for poetic effect. While many excellent painters of imposing buildings have been somewhat prosaic in their vision, Buchanan hunts down the telling fragments which may contain an essence of the whole.

In Buchanan’s watercolours time is neither in the present nor strictly in the past, yet his works do not deal in anything so simple as nostalgia either. Rather their time and special lighting emanate from the frozen moments of dreams and imaginings.

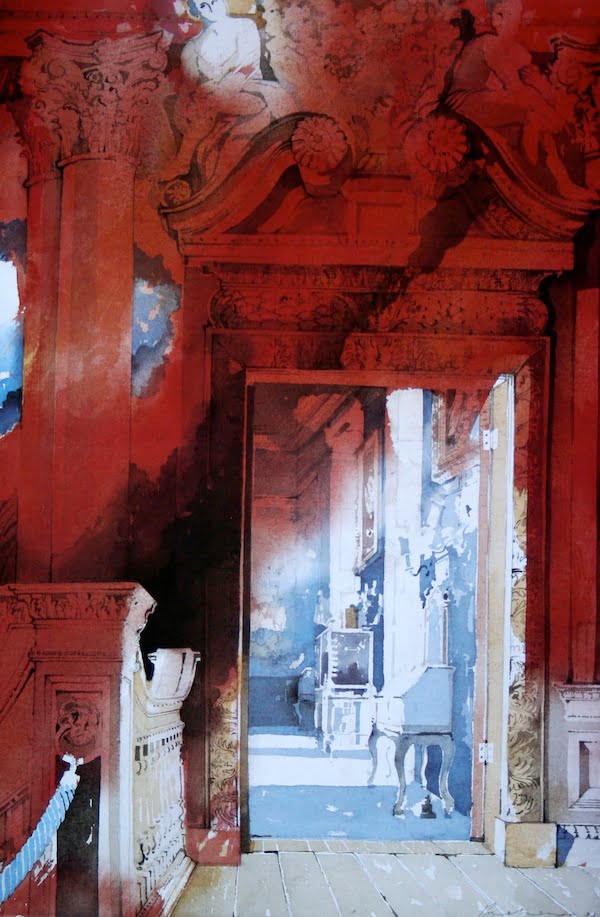

The new Petworth watercolours demonstrate the artists customary elegance and panache together with new strands of expression. The familiar vocabulary is there : accurate but economical drawing, unusual viewpoints, fierce contrasts of light and shadow, stirring washes of bold colour, a telling use of near silhouette. Petworths grandeur of scale and setting and the ornamental swagger of French Baroque inspire in the artist a new strand of haunting romanticism. Yet it is not just the abundance of rococo artefacts found at Petworth which prompts thoughts of Watteau and Tiepolo but Buchanan’s own inherent sense of theatre.

Some encountering Buchanan’s work for the first time may find it strange that an artist of the late twentieth century should produce imagery more redolent of followers of Rubens than of Rauschenberg, yet there is never a feeling of anachronism associated with Buchanan’s paintings. Rather they take on a valid role in an alternative history of artistic aspiration. Buchanan has created his own world and his own idiom arguing that the past has an inescapable influence on our innermost thoughts.

The Francis Kyle Gallery, London, 1992

REVIEWS

Yet another demonstration of unusual accomplishment by an artist who has been admired widely almost from student days. He uses the medium of watercolour with great compositional subtlety and sense of drama, mingling complex architectural details with simple shapes and silhouettes.

The Spectator 1992 Giles Auty

The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, 1991

INTRODUCTION

Shades of Scottish Classicism by Guy Peploe

Buchanan is an artist whose favoured medium is watercolour and whose subject matter is on the whole traditional. But one must be careful not to simply tack him on to the end of a long line of British topographical watercolourists. His vision is shaped as much by Modernism which his work seems at once to embrace and deny. The modern British school continues to throw up individualists and Buchanan is one more.

There is something of John Piper, as well as the Scottish blottist painters, Arthur Melville and JW Herald, but Buchanan has evolved his own vocabulary and his work is instantly recognisable. Some might describe it as traditional; I believe rather that it is a stalking horse for Modernism and that many, who might otherwise not look, come to a new understanding of modern art through Buchanan’s dramatic revelations.

REVIEWS

Hugh Buchanan paints buildings beautifully. If his rich watercolours don’t get you excited about architecture then there’s no hope.

Scotland on Sunday 1991 Clare Flowers

Buchanan has developed individual methods whereby paraphrasing is achieved and the integrity of each subject is preserved. Faintly reminiscent of Paul Klee semi abstract moves are often made towards geometric simplification: gable or entablature are distilled for their triangular strength; soft washes end in clean cut lines especially at corners and around rectangular windows; as in photographic double exposure, planes of tone subtly overlay each other.

The Scotsman – Edward Gage

Hugh Buchanan also displays prodigious technique. His chief interest is in architecture – in this case noble palaces and castles Fyvie, Falkland Holyrood Glamis et al – but on his own dramatic and romantic terms.

His buildings are wreathed in the mists of time or loom through the smoke of battle. They command improvisation of their history. Many might have been illustrations for Waverley novels; one at least a backdrop for the Edinburgh Military tattoo. A dowie loch stagnant in its own mysteries looks like the sort of water Gustav Mahler might have chucked himself into in a moment of total despair. Isolated architectural details are turned into powerful icons.

Scotland on Sunday 1991 W Gordon Smith

The Francis Kyle Gallery, London, 1990

REVIEWS

These paintings are much more than architectural topography. Dramatic use of light and shadow and swathes of strong colour energise and enliven even his smallest paintings. Hugh Buchanan has a reputed love of classical architecture but his approach is romantic more often than not. I have argued that young artists ought to be able to live largely from private patronage in the present economic climate, providing their work shows sense and merit. Buchanan’s work shows both, plus a high degree of virtuosity in his chosen medium; he has set himself on a path where both the challenges and achievements of his art are real and measurable. Buchanan’s art supports the case for concentration on the teaching of skills in art education. In the absence of these, the young artist brought up to think of himself as a young even more misunderstood Van Gogh sits about glumly waiting for his annual idea to come. Will the supposed expression of this idea involve dustbin lids, pig wire and other street cred materials? Most probably – for such an artist has but one hope; that of being noticed by the equally modish selectors, paid from the public purse, of shows such as the British Art Show. By contrast …Buchanan’s works enjoy merited popularity among discerning patrons accustomed to spending their own, rather than other people’s money.

Giles Auty – The Spectator, 1990

Here is complete mastery of the art of detail. If you say Turner was a topographical because he loved architecture, critics will tell you that it isn’t the architecture which makes Turner, but Turner himself. It is the same with Hugh. His evocations are unmistakably his own, full of his own grace and power and to call him topographical is to clip his wings unfairly. He loves smoke and clouds and cherubs and dark romantic colours. It is a language sometimes not a million years away from Tiepolo’s, The one in a dark chromatic key, the other light. Or you can think of John Piper whose dramatic colours in his pictures of Windsor Castle, once called the king to exclaim “pity you had such bad weather”. Like these others, Hugh is a superb technician, using the watercolour medium to suggest accurately and beautifully such difficult subjects as the difference between stone and marble or flowing water and rising steam.

Graham Hughes – Arts Review,1990

The Francis Kyle Gallery, London, 1988

REVIEWS

From the beginning of the watercolour medium, the British artist has always understood that it was ideal for expressing the nuances of light and atmosphere. Among contemporaries none has understood this better than Hugh Buchanan.

Arts Review 1988 Max Wykes – Joyce

Hugh Buchanan has always delighted in rays of sun. Sometimes this leads him to lapse into ‘rose tints’ but it also produces his most successful work.

The Times 1988 Alistair Hicks

The Scottish Gallery, 1987

REVIEWS

Hugh Buchanan’s exhibition radiates safety. It consists for the most part of drawings of neoclassical buildings and architectural details – mainly in Edinburgh, such as St Stephens Church, the Royal Scottish Academy and Dean Orphanage, which are then covered with bright patches of watercolour wash. One is left wondering why?

Neoclassicism has an austere strength but these works are weak and unchallenging. The few works devoted to the baroque period in Spain and in Germany are more interesting.

The Scotsman April 1987 Murdo Macdonald

Hugh Buchanan’s watercolours display all their customary elegance and panache.

These small works have a kind of high baroque splendour but the artist, unfortunately, seems unable to produce anything in a humbler key to provide a necessary contrast.

The Spectator April 1987 Giles Auty.

The Francis Kyle Gallery, London, 1986

INTRODUCTION

By Gervase Jackson – Stops

Hugh Buchanan’s art belongs to peculiarly Brittish tradition- that of the ‘picturesque’ as Burke saw it in his concept of the Beautiful and Sublime. As a way of looking at buildings it achieved classical expression in Turners interiors of Farnley and Petworth And Constables views of Salisbury cathedral and Wivenhoe park : a romantic, emotional response to history, finding human qualities in architecture and a feeling of time and place that is universal.

Like another young Scot who visited Rome 200 years ago – Robert Adam – Buchanan’s imagination has been fired by the seductive architecture of the south, the dome of the Salute dissolved in the rippling water of the Grand Canal, the cupola and balustrades of Borromini’s Roman churches, the arcaded courtyards of Florentine palaces. Like Adam he is fascinated by the way buildings can express movement, preferring the trumpets and drums of Vanbrugh to the polite minuets of the Palladians.

A constant sense of drama characterizes his compositions, never taken from the obvious viewpoint, but confronting problems of light and perspective head on. A battle scene on the staircase at Sudbury explodes into the picture, so that the room itself becomes an arena for the combatants; a bonfire in the porch of Christ Church Spitalfields sends smoke billowing up to the dizzy heights of Hawksmoors spire like a sacrifice at some ancient temple; a panelled door at Calke Abbey is thrust open almost violently, impelling the spectator into the great two storey hall with its long lines of family portraits.

His feeling for the theatre – and the narrow divide between life on stage and off – may also explain the sumptuous curtains, the damask backdrops to still lives, the vistas down corridors that speak of entries and exits, past and to come. Always there is a powerful understanding of the three – dimensional nature of great architecture: Eliot’s “inexplicable splendours of Ionian white and gold”. But so often too there is an elegiac note’ probing the sense of loss in the prismatic light filtering into a shuttered library or a ghost like ancestor reflected in a rococo pier glass.

Whether at the Escorial or the Grand Palais, a folly in Buckinghamshire or a country churchyard in Fife, Hugh Buchanan’s intensely personal vision takes us beyond the buildings themselves to the spirits that created them – beyond the formal and classical, to the Beautiful and Sublime.

REVIEWS

Today the word “ Picturesque” summons up visions of maiden aunts in beekeepers hats sketching washy views of Windermere, or picture postcards of Tintagel against impossibly blue skies. But it was not always so. In the 18th century it implied a way of looking at buildings and landscapes with all the seriousness of Burkes theories on the beautiful and the sublime.Some of John Pipers early work can be seen as a revival of this tradition.

Hugh Buchanan’s watercolours show the development of a rare talent in this sphere, an ability to look the past straight in the face, yet without compromising a vivid imagination and without letting mere topography overcome a highly individual sense of energy and drama.

Hugh Buchanan’s strength lies in the unconventionality of his chosen subjects. Never taking the obvious viewpoints he his particularly concerned way solid architectural elements are dissolved by colour and light, by the sinuous forms of rococo plasterwork against the line of a classical cornice, or the folds and tassels of a heavy damask curtain against bolection panelling.

Their poetry, as much as their clarity of vision and sureness of taste is what puts these watercolours in a class of their own. Country houses and churches temples and follies ballrooms and back passages have found a chronicler able to evoke the spirit of the past in the age of the post modern.

COUNTRY LIFE May 1986 Gervase Jackson – Stops

The Scottish Gallery, 1984

INTRODUCTION

Poetry of the picturesque nicely disturbed – Edward Gage

Hugh Buchanan is a gifted young artist whose painting presents few difficulties for the viewer. Youth here is not in rebellion, but seems determined rather to beguile. In both his choice of theme , which is largely architectural, and his easy familiarity with the traditional medium of pure watercolour he engages the attention of a wide public.

His latest work reveals a subtle but significant change of emphasis in his vision.

The general impression is discarded in favour of focus and detail, description gives way to more pressing matters of improvisation and arrangement, the theme becomes a motif. Classical and Baroque architecture of course provide the painter with a library of forms already well ordered by mans design, motifs which seen in different contexts and atmospheres may be conveniently isolated , rephrased or even rearranged according to mood.

Here these include fragments of facades or interiors, domes, pillars, doorways balconies arches pediments, mouldings, gravestones pulpits and organ lofts which Buchanan has sniffed out in Rome, Austria and Bavaria as well as his native city.

Such motifs are visualised very much in the terms of his volatile medium and his relaxed handling conveys delight as he rejoices in every flood stain or blot. Colour often restricted to soft reds and blues is emotive rather than descriptive, while romantic sensations of dissolution or decay invade elements that are formally classical.

Careworn surfaces shift, vertical lines lean dangerously, a curtain mysteriously fashions an alcove in cahoots with a column. The poetry of the picturesque has been nicely disturbed.

REVIEWS

Hugh Buchanan is a 26 year old Scots artist whose passion is the baroque. Not for him the cut and thrust of modern art with its frenetic searching after New Imagine, New Expressionism, New anything. He works in the established convention of good, solid even sometimes beautiful architectural draughtsmanship recording the lush interiors of baroque churches in Italy, Austria and Bavaria with that skilful blend of accuracy and imagination which the public love.

So its not surprising that all the pretty pictures at the Scottish Gallery were snapped up fast, leaving the more interesting , more restrained studies of the gateway and iron railings of Edinburgh’s Old College or the plain stone slab doorway of the Sheriff Court unspoken for.

Of course being buildings from the Athens of the north they are quite rightly captured in sombre grey. In contrast the flamboyant ceilings, altars, cupolas and marble busts of St Ignazio in Rome or St Maria Alm in Austria look appealingly theatrical suffused in glowing pink and blue watercolour washes.

Buchanan’s undoubted technical skill could be a handicap if it prevents him from exploring new avenues. However some recent spirited palm tree studies from Barbados hint at future developments.

The Glasgow Herald – 1984 – Clare Henry

The Henderson Gallery, Edinburgh, 1982

REVIEWS

Effects of light and shade absorb Hugh Buchanan. It is unusual to find a young painter taking up watercolour and using it so purely for he proves to be a gentle practitioner, describing his subjects with delicate washes of coloured light and atmosphere, creator of idyllic fragments, dreamy nuances, subtle airs and architectural graces.

Edward Gage THE SCOTSMAN Jan 1982

Cale Art, London, 1982

REVIEWS

Whatever you are doing drop it and go and see Hugh Buchanan’s rich, beautifully planed watercolours on the theme of the sphere in architecture from Rome’s pantheon to London’s power stations. You have until October 14 to see these new works from a burgeoning talent.

Interiors Oct 1982