Lineaments of Light

The Francis Kyle Gallery, London, 2012

REVIEWS

THE MYSTERY OF FALLING LIGHT

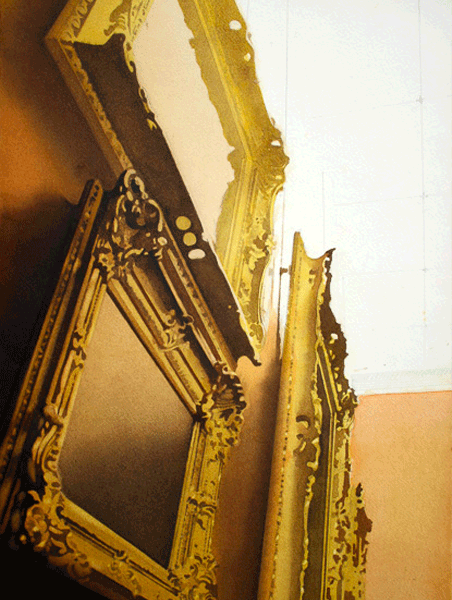

At the heart of Hugh Buchanan’s new sequence of interiors in watercolour are several paintings of picture frames, observed in the Palace of Versailles and at Arniston House in Midlothian. While the paintings within their frames melt into obscurity, their mouldings and those of nearby architraves and cornices block, divert or play with light in a multiplicity of strange and surprising ways. Luminous and darkly glowing, these are paintings which, beyond context and content, celebrate the mystery and poetry of falling light.

An early example of this from antiquity is Nero’s Golden House in Rome. The octagonal domed and top-lit hall, similarly stressing void not mass, opens into five rooms bathed in a concealed light from oblique slots above the octagonal dome, speaking for the pre-eminent role assigned in an interior scheme to falling light. About sixty years later, Hadrian’s Pantheon in Rome of c.118 is one of the most dramatic top-lit buildings of all. Lit only by the opening at the apex of its dome, its appearance shifts as the sun moves round, constantly illuminating different parts of the interior.

The architecture of surprise and of the drama of light and shadow re-emerged in the Baroque period when Bernini exploited light from hidden sources, as in his Cornaro Chapel of the 1640s at Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome. Here, he lit his dramatic group of St Teresa in Ecstasy by a concealed window of amber glass and by baffles funnelling natural light towards it. By then, Hadrian’s Villa had become ruinous, so that light could now penetrate through irregular breaks in its formerly solid groin vaults and complex domes, providing inspiration for Piranesi, whose captivating engravings of Roman ruins from the 1740s to the 70s always exploited the romantic effects of light and shade. He was also quick to seize the implications of this for modern buildings as in his own designs for St John Lateran where light falls from concealed, sliced-off semi-domes. Piranesi, who gave some of his engravings to the youthful architect John Soane was in turn a great admirer of Robert Adam, whose published engraving of the vaulted drawing room at Derby House, Grosvenor Square (1773-4), can, when viewed with half-closed eyes, look almost identical to his watercolour view of an ancient Roman interior with a ruined vault.

In their mood Hugh Buchanan’s paintings, mostly of eighteenth-century interiors in nine great houses in England and Scotland, have a distinguished parallel in the work of Soane’s friend Turner, as well as in the evocative paintings of Soane’s designs by his amanuensis, the architect Joseph Gandy. The poet James Thomson inherited from Newton the belief, shared by Soane, that the golden light of yellow is the most luminous and beautiful of all. This is the amber light with which Soane bathed interiors such as his mausoleum at Dulwich College Gallery, designed to create a mysterious contrast to the daylight in the picture gallery from which it opens.

It is this same effect which finds an echo in Buchanan’s watercolours of a corner of the Red Drawing Room at Hopetoun House, West Lothian, as remodelled by John Adam in the 1750s for the 2nd Earl of Hopetoun. In this hypnotic sequence, light floods in from one of the west-facing windows but is interrupted by the Holland blind so that the surface of the Van Dyck portrait of the Marquis di Spinola has pools of shadow and of golden light. Buchanan perceptively shows the conjunction of different sources of illumination, one from the sun and the other from the picture-lights over the paintings which also light the dust hanging in the air.

At Ham House, Surrey, created in the 1630s for William Murray, 1st Earl of Dysart, Buchanan gives us two watercolours of the magnificently carved balustrades. A certain haunting quality in his approach seems to suggest the imminent emergence of the ghost of a woman in white in the misty and somehow mysterious light coming from the mullioned window on the landing. At Wilton House, Wiltshire, Buchanan paints the Single and Double Cube Rooms, both facing south, the first of these flooded in light, whereas an arrangement of the curtains in the Double Cube Room creates a shadowy golden light. In two of the three paintings of the Single Cube Room, the gleaming marble surface of a pier table reflects, upside down, two portraits: a puzzling hall of mirrors.

‘There are two kinds of light,’ writes James Thurber in one of the artist’s favourite quotations: ‘the glow that illumines, and the glare that obscures,’ an aside which well defines Buchanan’s mastery of this most poetic and elusive idiom.

Professor David Watkin