Shine

Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh, 2015

REVIEW

ROY STRONG talks to HUGH BUCHANAN about his new work

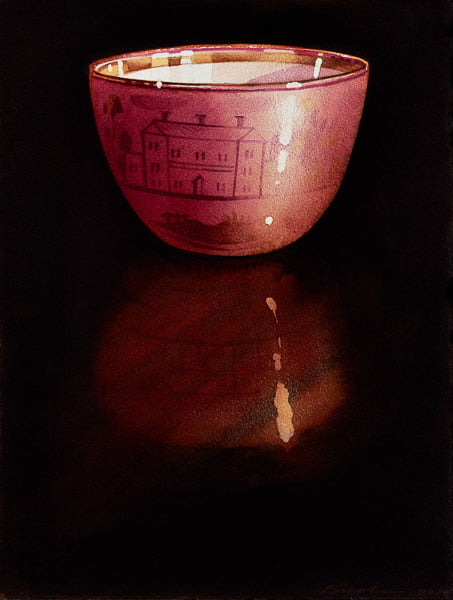

Hugh, there is something haunting about your work. I suppose that this new group of watercolours could be called Reflections for most objects here take on a double life. The first is at the top of the space recording their actuality in a manner which, at first glance, seems to upset the balance of the composition but, no, for the eye is then led downwards for the item to be reborn like a ghost in a polished surface.

HB. The reflections supply the dynamic to compositions that would otherwise be lifeless. The eye can wander down and loose itself in the gloom, navigating by the random white flecks, in the same way, I hope, that one could loose oneself in a Claude Lorrain landscape -albeit in this case an upside down one, with the reflected gloom playing the same role as all of those endlessly receding blue hills. Also in my mind were the dark reflections of Richard Wilson’s sump oil filled room first shown in Edinburgh in 1987.

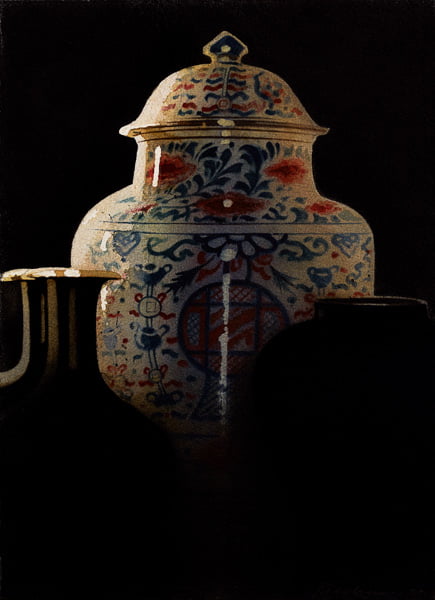

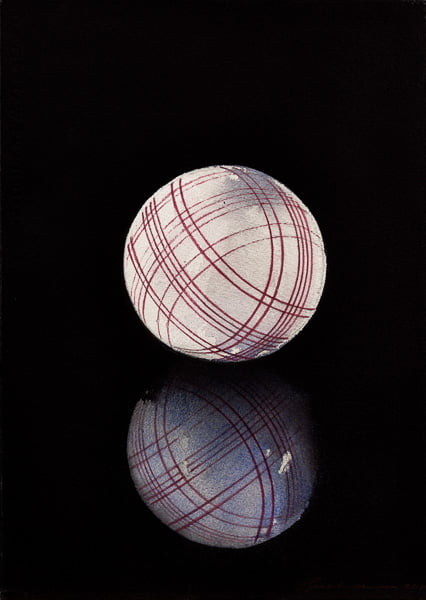

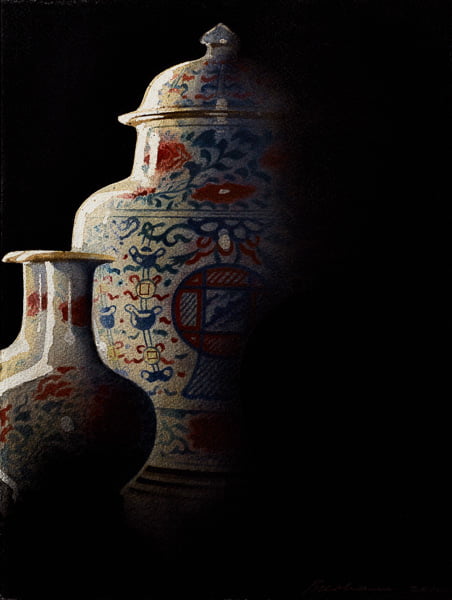

RS. It’s odd what catches your eye, sometimes it can be the elegant and fragile beauty of a blue and white Chinese scent bottle and yet in others we are confronted with the sentimental kitsch of porcelain figures of children in army uniform. So I’m often left wondering why you have chosen this or that to be immortalised transforming, for example, a common ball of string into an icon. Why bother?

HB. Two years ago I visited the Roy Lichtenstein exhibition at Tate Modern and was struck by his Ball of Twine depicted in black and white and plonked down right in the middle of the canvas. A form of composition Lichtenstein described as ‘Islanding’.

His other subjects included a car tyre and a golf ball. I wondered if I could bring this same kind of direct approach to my subject matter, which is firmly stuck in the 1750’s. I cannot really account for this, but I do remember even as a schoolboy being aware of your exhibition The Destruction of The Country House at the V&A in 1974 and relating it directly to the destruction that had recently been wrought in Edinburgh with the construction of the monstrous St James’s Centre and the consequent loss of St James’s Square. And so those little figurines although a bit Jeff Koons, although a bit kitsch, although a bit sentimental and perhaps precisely because of these flaws, become in my mind plaintive symbols of loss and regret.

RS. Are they just exercises in bravura technique or is there something more complex at the back of your mind. However technically proficient they are as instances of still life painting they have something beyond which sticks in the mind’s eye.

HB. Well I certainly like to set myself technical challenges and hopefully the qualities that I’m trying to attain will emerge from their resolution. I noticed recently for example that if I put highlights on the shaded side of a piece of porcelain it attains a more vivid reality. So I think that technique and substance should be indivisible. If your drawing is good and your paper is strong, watercolour is a little more forgiving than some people imagine, but it’s all about meticulous planning – which colours to use and in what order to apply them. It is often said that an artist succeeds when he has transmitted what is in his head onto the page. I like to go one stage further and be surprised by the result myself

RS. And then there’s the interiors or rather sections of rooms. In these you seem to be obsessed by the impact of light of an intensity and strength that would give any museum curator palpitations.

HB I’m very particular about light and have a sort of forensic interest in its idiosyncrasies. That is the real subject of my work. The rest is just a frame to hang it on. Sunlight is obviously different in its altitude and strength every day of the year. Strong midsummer light hardly enters a room at all whereas the fingers of midwinter light reach right back to the farthest wall. On an overcast day it is noticeable that reflections become more intense. So there is always something to work with even on the gloomiest day.

RS. And then there’s the dialogue with the camera’s lens which focuses in and then suddenly draws back. This is work that is both beautiful and tantalising but how important is the camera in your work ?

HB I used to be rather puritanical in never using a camera but I came gradually to realise that working in the area that I do – that is to say interiors – I was deliberately limiting myself to the obvious – after all there are only so many places that you can sit in a room, and condemning myself to repeat the compositions that Caddell, Pride and Sargent had done so well before. By using a camera I can look down from a step ladder or look up lying on the floor I can also freeze for ever those fleeting effects of light which in twenty minutes have quite disappeared.

RS In these there’s a love affair with emptiness, an appreciation that any room has a life of its own when no one is in it. And that life in the main is made up of constantly shifting shafts of light intruding into the muted gloom.

HB As you have said before Roy, the Country House represents the most superb visual apparatus. Having been brought up in a glass box surrounded by Conran furniture. I was immediately captivated by the drama and textures of historic interiors. The context in which I was introduced to that world was through the medium of the National Trust which has so effectively nationalised that aspect of our heritage that it has perhaps inadvertently invented a new aesthetic which I have picked up on. That is to say the aesthetic of the Empty House, a sort of Gormenghast peopled by ghosts and dust motes to which we can all legitimately claim ownership.

Nobody could accuse the Scottish painter Hugh Buchanan of being a fashion victim. Over the past 30 years he has stuck firmly to his distinctive style. Buchanan is best known for his watercolours of grand, sweeping interiors, and for capturing the effects of light. This selection of recent works will only enhance his status. Best on show here is Newhailes Interior a painting that tips its hat to Patrick Caulfield. Less dramamtic but just as alluring are a clutch of paintings of vases and figurines. If the matter sometimes seems kitsch, the effect is anything but. Buchanan is far from precious and has depicted everything from balls of string to tins of Guinness in a similar style. The black backgrounds of these still lifes accentuate the objects’ brighter colours and provides an eerie counterpoint.

The Week 28 February 2015